“A HARLOT’S PROGRESS - PLATE 3” -

WILLIAM HOGARTH - Satirical Etching Engraving

25 1/8 x 19 1/24 inches. Plate image: 15 3/8 x 12 9/16 inches. Inscription content: Lettered below image, "Plate 3./Wm. Hogarth invt. pinxt. et sculpt."

From the retired Mitch Moore Gallery Inc, NYC. Unmatted, never framed or displayed. Image area is in very good frameable vintage condition.

Description Plate 3

A shabby room in Drury Lane; Moll is rising late, attended by a serving-woman who has lost part of her nose to syphilis; in the background, the magistrate, John Gonson, enters quietly with officers to arrest her; pinned to the window frame are prints of Captain Mackheath (the hero of "The Beggar's Opera") and Dr Sacheverell (the High Anglican clergyman impeached in 1710), the hat-box of James Dalton, highwayman, rests above the bed, and one of several beer tankards on the floor carries the name of a local tavern . 1732

Etching and engraving

About the artist: WILLIAM HOGARTH

A celebrated painter of satirical commentaries on contemporary English life, Hogarth was primarily known in the eighteenth century through the publication and subscription sale of prints her personally engraved after his own painted compositions. Hogarth often designed his "Modern Moral Subjects" in narrative series in which he lampooned the foibles of his fellow Englishmen and women throughout society.

Hogarth achieved his first great success with A Harlot's Progress, a narrative cycle of six scenes depicting the moral dissolution of a once-innocent country girl through the life of a prostitution in London.

Painter, draughstman and engraver; b. London 1697; d. there 1764; son in law of Thornhill; trained as ornamental engraver; studied drawing at Vanderbank's Academy; active as a painter from 1728/9, specializing in portraits and genre to mid 1730s; engraved series of moral subjects 1732 'The Harlot's Progress'

The plates[edit]

Plate 1

Moll Hackabout arrives in London at the Bell Inn, Cheapside

The protagonist, Moll Hackabout, has arrived in London's Cheapside. Moll carries scissors and a pincushion hanging on her arm, suggesting that she sought employment as a seamstress. Instead, she is being inspected by the pox-ridden Elizabeth Needham, a notorious procuress and brothel-keeper, who wants to secure Moll for prostitution. The notorious rake Colonel Francis Charteris and his pimp, John Gourlay, look on, also interested in Moll. The two stand in front of a decaying building, symbolic of their moral bankruptcy. Charteris fondles himself in expectation.

Londoners ignore the scene, and even a mounted clergyman ignores her predicament, just as he ignores the fact of his horse knocking over a pile of pans.

Moll appears to have been deceived by the possibility of legitimate employment. A goose in Moll's luggage is addressed to "My lofing cosen in Tems Stret in London": suggesting that she has been misled; this "cousin" might have been a recruiter or a paid-off dupe of the bawdy keepers. Moll is dressed in white, in contrast to those around her, illustrating her innocence and naiveté. The dead goose in or near Moll's luggage, similarly white, foreshadows Moll's death as a result of her gullibility.

The inn sign, with a picture of a bell, may refer to the belle (French for beautiful woman) who has newly arrived from the country. The teetering pile of pans alludes to Moll's imminent "fall". The goose and the teetering pans also mimic the inevitable impotence that ensues from syphilis, foreshadowing Moll's specific fate.

The composition resembles that of a Visitation, i.e. the visit of Mary with Elizabeth as recorded in the Gospel of Luke 1:39–56.

Plate 2

Moll is now a kept woman, the mistress of a wealthy merchant

Moll is now the mistress of a wealthy Jewish merchant, as is confirmed by the Old Testament paintings in the background which have been considered to be prophetic of how the merchant will treat Moll in between this plate and the third plate. She has numerous affectations of dress and accompaniment, as she keeps a West Indian serving boy and a monkey. The boy and the young female servant, as well as the monkey, may be provided by the businessman. The presence of the servant, the monkey and the mahogany table of tea things all suggest the merchant's wealth has been made in the colonies.[10] She has jars of cosmetics, a mask from masquerades, and her apartment is decorated with paintings illustrating her sexually promiscuous and morally precarious state. She pushes over a table to distract the merchant's attention as a second lover tiptoes out.

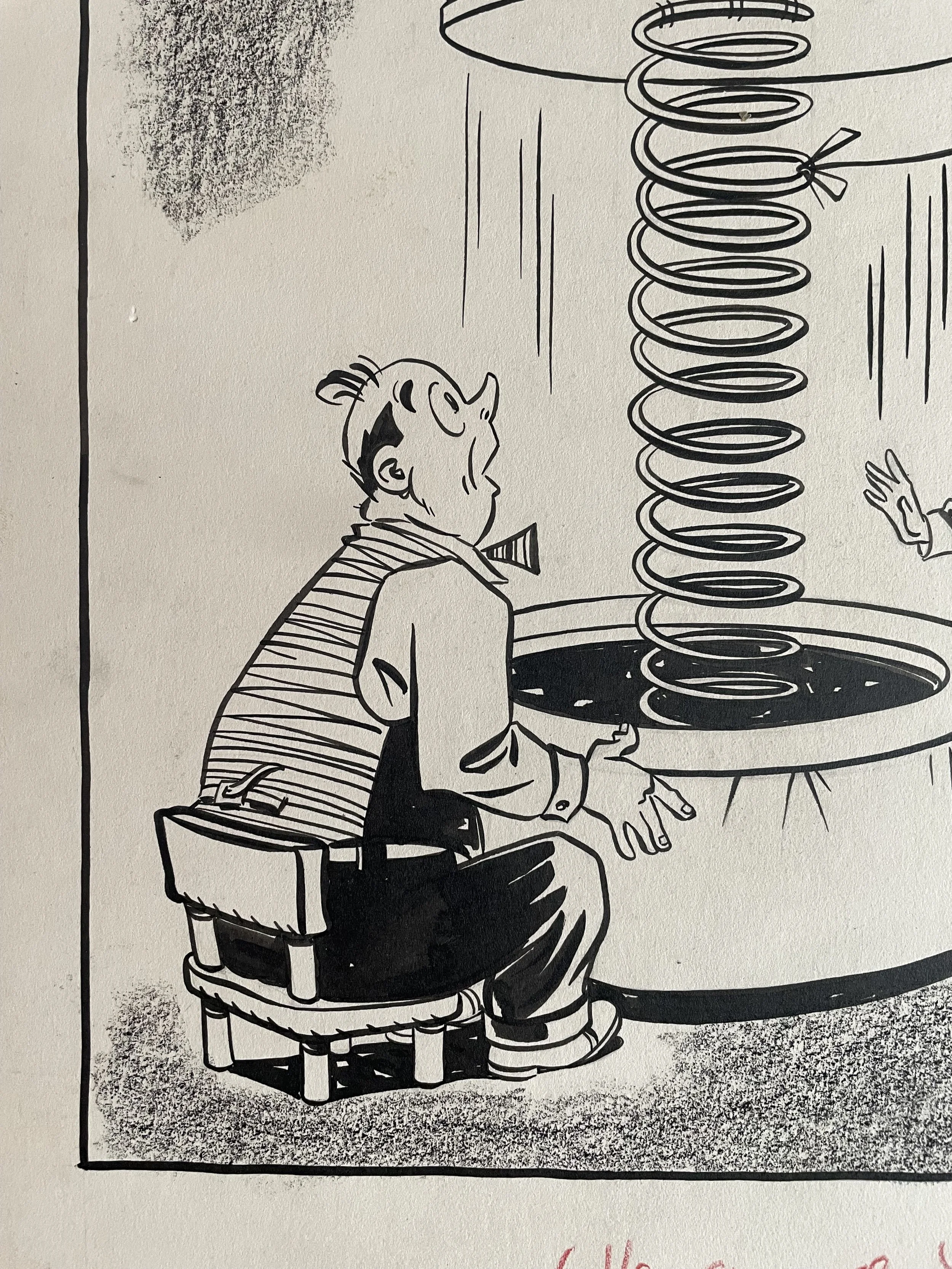

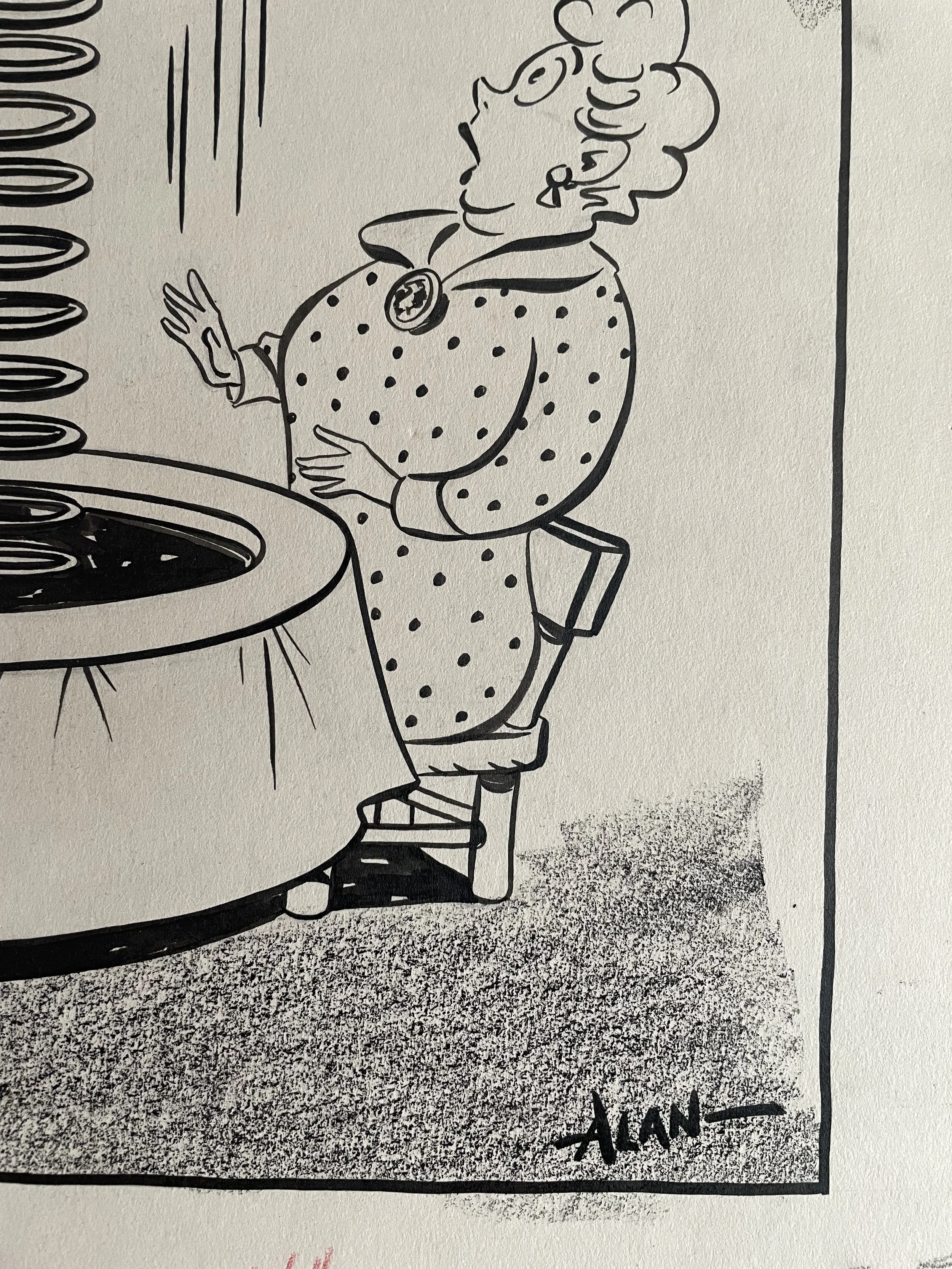

Plate 3

Moll has gone from kept woman to common prostitute

Moll has gone from kept woman to common prostitute. Her maid is now old and syphilitic, and Henry Fielding, in Tom Jones (2:3), would say that the maid looks like his character of Mrs. Partridge. Her bed is her only major piece of furniture, and the cat poses to suggest Moll's new posture. The witch hat and birch rods on the wall suggest either black magic, or more importantly that prostitution is the devil's work. Her heroes are on the wall: Macheath from The Beggar's Opera and Henry Sacheverell, and two cures for syphilis are above them.

The wig box of highwayman James Dalton (hanged on 11 May 1730) is stored over her bed, suggesting a romantic dalliance. The magistrate, Sir John Gonson, with three armed bailiffs, is coming through the door on the right side of the frame to arrest Moll for her activities. Moll is showing off a new watch (perhaps a present from Dalton, perhaps stolen from another lover) and exposing her left breast. Gonson, however, is fixed upon the witch's hat and 'broom' or the periwig hanging from the wall above Moll's bed.

The composition satirically resembles that of an Annunciation, i.e. the announcement by the angel Gabriel to the Virgin Mary that she would conceive and become the mother of Jesus, the Son of God, as recorded in the Gospel of Luke 1:26–39.

Plate 4

Moll beats hemp in Bridewell Prison

Moll is in Bridewell Prison. She beats hemp for hangman's nooses, while the jailer threatens her and points to the task. Fielding would write that Thwackum, one of Tom Jones's sadistic tutors, looked precisely like the jailer (Tom Jones 3:6). The jailer's wife steals clothes from Moll, winking at theft. The prisoners go from left to right in order of decreasing wealth.

Moll is standing next to a gentleman, a card-sharp whose extra playing card has fallen out, and who has brought his dog with him. The inmates are in no way being reformed, despite the ironic engraving on the left above the occupied stocks, reading "Better to Work/ than Stand thus." The person suffering in the stocks apparently refused to work.

Next is a woman, a child who may have Down syndrome (belonging to the sharper, probably), and finally a pregnant African woman who presumably "pleaded her belly" when brought to trial, as pregnant women could not be executed or transported. A prison graffito shows John Gonson hanging from the gallows. Moll's servant smiles as Moll's clothes are stolen, and the servant appears to be wearing Moll's shoes.

Plate 5

Moll dying of syphilis

Moll is now dying of syphilis. Dr. Richard Rock on the left (black hair) and Dr. Jean Misaubin on the right (white hair) argue over their medical methods, which appear to be a choice of bleeding (Rock) and cupping (Misaubin). A woman, possibly Moll's bawd and possibly the landlady, rifles Moll's possessions for what she wishes to take away.

Meanwhile, Moll's maid tries to stop the looting and arguing. Moll's son sits by the fire, possibly sick with syphilis as well. He is picking lice or fleas out of his hair. The only hint as to the apartment's owner is a Passover cake used as a fly-trap, implying that her former keeper is paying for her in her last days and ironically indicating that Moll will, unlike the Israelites, not be spared. Several opiates ("anodynes") and "cures" litter the floor. Moll's clothes seem to reach down for her as if they were ghosts drawing her to the afterlife.

Plate 6

Moll's wake

In the final plate, Moll is dead, and all of the scavengers are present at her wake. A note on the coffin lid shows that she died aged 23 on 2 September 1731. The parson spills his brandy as he has his hand up the skirt of the girl next to him, and she appears pleased. A woman who has placed drinks on Moll's coffin looks on in disapproval. Moll's son plays ignorantly. Moll's son is innocent, but he sits playing with his top underneath his mother's body, unable to understand (and figuratively fated to death himself).

Moll's madam drunkenly mourns on the right with a ghastly grinning jug of "Nants" (brandy). She is the only one who is upset at the treatment of the dead girl, whose coffin is being used as a tavern bar. A "mourning" girl (another prostitute) steals the undertaker's handkerchief.

Another prostitute shows her injured finger to her fellow whore, while a woman adjusts her appearance in a mirror in the background, even though she shows a syphilitic sore on her forehead. The house holding the coffin has an ironic coat of arms on the wall displaying a chevron with three spigots, reminiscent of the "spill" of the parson, the flowing alcohol, and the expiration of Moll. The white hat hanging on the wall by the coat of arms is the one Moll wore in the first plate, referring back to the beginning of her end.